An absurdist, minimalist masterpiece, Kaneto Shindo’s 1964 film remains a compelling must-watch 60 years after its release.

It’s a deceptively simple premise, predominately inspired by a Buddhist parable. In the midst of a 14th century civil war in Japan, an older woman – whose son is fighting in the war – and her daughter in law live in a remote hut, waiting for the war to end and for their loved one to return. They survive by indiscriminately hunting down wounded soldiers and exchanging their equipment for food with a seedy local trader. There is almost nothing else for them at this time except pure survival; a ruthless endeavour at the mercy of capitalism. That is until the return of a buffoonish neighbour named Hachi disrupts the temporary lives they have forged. He ostensibly informs the two women that the son and husband that they have been awaiting was killed in the war. His demeanour instantly makes him an untrustworthy source of information, but so too does the lack of any real emotional response from either woman. The older woman warns her daughter in law to stay away from Hachi, but they soon begins a sexual relationship after multiple advances from him. This enrages the older woman, as she sees it as a threat to the very foundation of her existence, so, after a chance encounter with a samurai, she takes it upon herself to restore the order.

The film is particularly progressive for the time period and there’s a primal intensity of sexual desire lingering in every scene as soon as we’re introduced to Hachi. These scenes are tame by today’s standards, but the film was initially banned in the UK, until it was awarded an X certificate in 1968 after sufficient cuts were made. Eventually, the older woman attempts to seduce Hachi herself, but she suffers a humiliating and undignified rejection. She pleads with him not to take her daughter in law away as she needs her to help hunt soldiers. This feels like she’s trying to justify her attempted seduction to herself, rather than Hachi, as it feels like her advances are motivated more by jealousy than pragmatism. There’s a mortality aspect to all these proceedings as well. The older woman is frequently criticised and almost ostracised for being just that – old. Multiple characters make reference to her age and there’s an underlying sense of her wanting to maintain her relevancy as the people in her life disappear around her.

The literal translation of Onibaba is “demon hag”, and it earns that title from final 20 minutes or so of the film. Using the mask of a dead samurai, the older woman attempts to scare her daughter in law as she tries to sneak out in the middle of the night to meet Hachi. She tries to convince her that she is being haunted by a demon as punishment for her adultery. While this temporarily works, eventually the girl ignores the warnings and cannot resist the temptation to be back with her lover. The older woman concedes and stops her efforts, but finds that the mask she has been using has now permanently fixed itself to her face. The woman begs her daughter in law to help her remove the mask and won’t interfere with her affair anymore if she helps her. Like the samurai who previously wore the mask, the older woman’s face is now permanently disfigured; almost demon-like in appearance.

The scenes where the older woman dons the mask are brilliantly realised set-pieces. Amongst the striking imagery of the beautiful grass and dramatic rain, the woman seemingly glides across the landscape to haunt the young in-law, in what is probably one of the film’s most memorable shots. It’s a powerful shift in tone which subverts the earlier moral eroticism in favour of something supernatural and spiritual. While it’s more jidaigeki (period drama) than true horror film, Onibaba remains an influential milestone of the genre. When pleading with the younger woman to help her remove the mask, the crazed expression of desperation across its face adds a horribly unsettling feeling to an already uncomfortable scene. The camera, unflinching and intimate, lingers on that expression which would become the most well-known iconography of the movie.

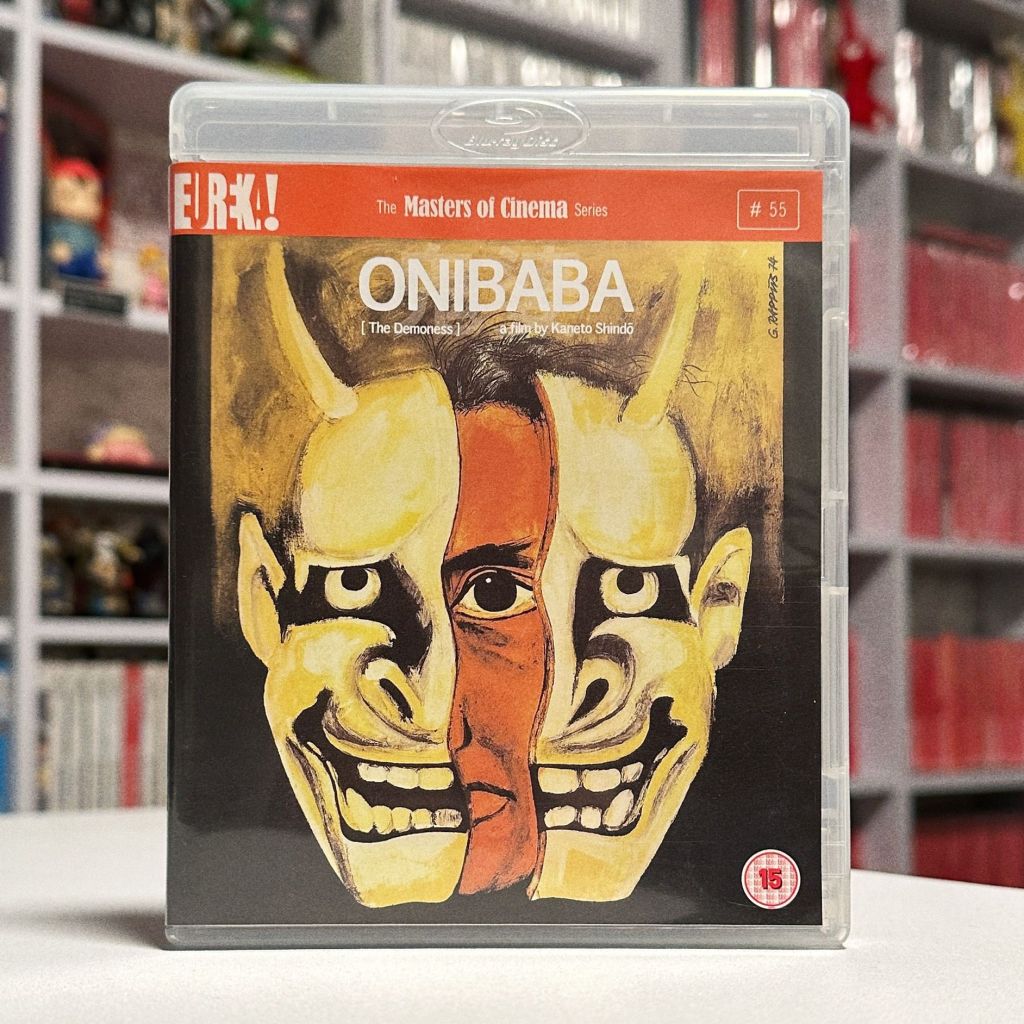

Of the 48 films that Shindo directed, Onibaba arguably remains the most famous and revered of all his works. It is available courtesy of Eureka as part of their Masters of Cinema series.